Writing a Chip-8 Emulator from Scratch in JavaScript

I spent a good portion of my childhood playing emulated NES and SNES games on my computer, but I never imagined I'd write an emulator myself one day. However, Vanya Sergeev challenged me to write a Chip-8 interpreter to learn some of the basic concepts of lower-level programming languages and how a CPU works, and the end result is a Chip-8 emulator in JavaScript that I wrote with his guidance.

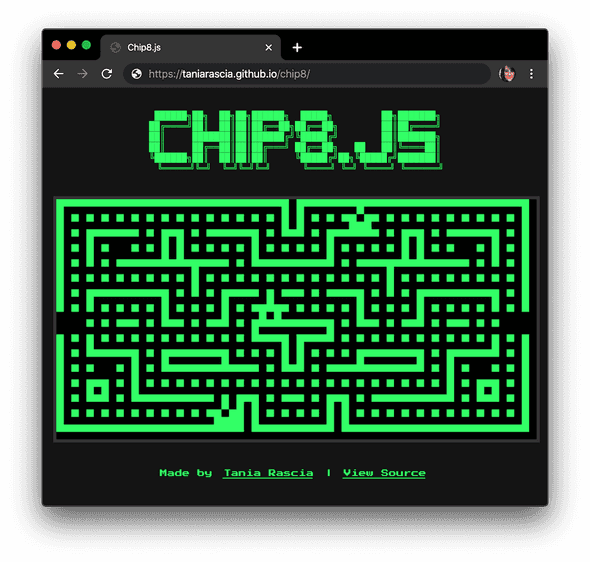

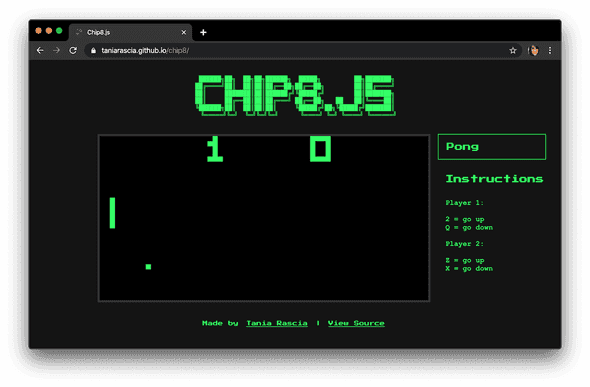

Although there are endless implementations of the Chip-8 interpreter in every programming language imaginable, this one is a bit unique. My Chip8.js code interfaces with not just one but three environments, existing as a web app, a CLI app, and a native app.

You can take a look at the web app demo and the source here:

There are plenty of guides on how to make a Chip-8 emulator, such as Mastering Chip8, How to Write an Emulator, and most importantly, Cowgod's Chip-8 Technical Reference, the primary resource used for my own emulator, and a website so old it ends in .HTM. As such, this isn't intended to be a how-to guide, but an overview of how I built the emulator, what major concepts I learned, and some JavaScript specifics for making a browser, CLI, or native app.

What is Chip-8?

I had never heard of Chip-8 before embarking on this project, so I assume most people haven't either unless they're already into emulators. Chip-8 is a very simple interpreted programming language that was developed in the 1970s for hobbyist computers. People wrote basic Chip-8 programs that mimicked popular games of the time, such as Pong, Tetris, Space Invaders, and probably other unique games lost to the annuls of time.

A virtual machine that plays these games is actually a Chip-8 interpreter, not technically an emulator, as an emulator is software that emulates the hardware of a specific machine, and Chip-8 programs aren't tied to any hardware in specific. Often, Chip-8 interpreters were used on graphing calculators.

Nonetheless, it's close enough to being an emulator that it's usually the starting project for anyone who wants to learn how to build an emulator, since it's significantly more simple than creating an NES emulator or anything beyond that. It's also a good starting point for a lot of CPU concepts in general, like memory, stacks, and I/O, things I deal with on a daily basis in the infinitely more complex world of a JavaScript runtime.

What Goes Into a Chip-8 Interpreter?

There was a lot of pre-learning I had to do to even get started understanding what I was working with, since I had never learned about computer science basics before. So I wrote Understanding Bits, Bytes, Bases, and Writing a Hex Dump in JavaScript which goes over much of that.

To summarize, there are two major takeaways of that article:

- Bits and Bytes - A bit is a binary digit -

0or1,trueorfalse, on or off. Eight bits is a byte, which is the basic unit of information that computers work with. - Number Bases - Decimal is the base number system we're most used to dealing with, but computers usually work with binary (base 2) or hexadecimal (base 16).

1111in binary,15in decimal, andfin hexadecimal are all the same number. - Nibbles - Also, 4 bits is a nibble, which is cute, and I had to deal with them a bit in this project.

- Prefixes - In JavaScript,

0xis a prefix for a hex number, and0bis a prefix for a binary number.

I also wrote a CLI snake game in preparation of figuring out how to work with pixels in the terminal for this project.

A CPU is the main processor of a computer that executes the instructions of a program. In this case, it consists of various bits of state, described below, and an instruction cycle with fetch, decode, and execute steps.

- Memory

- Program counter

- Registers

- Index register

- Stack

- Stack pointer

- Key input

- Graphical output

- Timers

Memory

Chip-8 can access up to 4 kilobytes of memory (RAM). (That's 0.002% of the storage space on a floppy disk.) The vast majority of data in the CPU is stored in memory.

4kb is 4096 bytes, and JavaScript has some helpful typed arrays, like Uint8Array which is a fixed-size array of a certain element - in this case 8-bits.

let memory = new Uint8Array(4096)You can access and use this array like a regular array, from memory[0] to memory[4095] and set each element to a value up to 255. Anything above that will fall back to that (for example, memory[0] = 300 would result in memory[0] === 255).

Program counter

The program counter stores the address of the current instruction as an 16-bit integer. Every single instruction in Chip-8 will update the program counter (PC) when it is done to go on to the next instruction, by accessing memory with PC as the index.

In the Chip-8 memory layout, 0x000 to 0x1FF in memory is reserved, so it starts at 0x200.

let PC = 0x200 // memory[PC] will access the address of the current instruvtion*You'll notice the memory array is 8-bit and the PC is a 16-bit integer, so two program codes will be combined to make a big endian opcode.

Registers

Memory is generally used for long-term storage and program data, so registers exist as a kind of "short-term memory" for immediate data and computations. Chip-8 has 16 8-bit registers. They're referred as V0 through VF.

let registers = new Uint8Array(16)Index register

There is a special 16-bit register that accesses a specific point in memory, referred to as I. The I register exists mostly for reading and writing to memory in general, since the addressable memory is 16-bit as well.

let I = 0Stack

Chip-8 has the ability to go into subroutines, and a stack for keeping track of where to return to. The stack is 16 16-bit values, meaning the program can go into 16 nested subroutines before experiencing a "stack overflow".

let stack = new Uint16Array(16)Stack pointer

The stack pointer (SP) is an 8-bit integer that points to a location in the stack. It only needs to be 8-bit even though the stack is 16-bit because it's only referencing the index of the stack, so only needs to be 0 thorough 15.

let SP = -1

// stack[SP] will access the current return address in the stackTimers

Chip-8 is capable of a glorious single beep as far as sound goes. To be honest, I didn't bother implementing an actual output for the "music", though the CPU itself is all set up to interface properly with it. There are two timers, both 8-bit registers - a sound timer (ST) for deciding when to beep and a delay timer (DT) for timing some events throughout the game. They count down at 60 Hz.

let DT = 0

let ST = 0Key input

Chip-8 was set up to interface with the amazing hex keyboard. It looked like this:

┌───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ C │

│ 4 │ 5 │ 6 │ D │

│ 7 │ 8 │ 9 │ E │

│ A │ 0 │ B │ F │

└───┴───┴───┴───┘In practice, only a few of the keys seem to be used, and you can map them to whatever 4x4 grid you want, but they're pretty inconsistent between games.

Graphical output

Chip-8 uses a monochromatic 64x32 resolution display. Each pixel is either on or off.

Sprites that can be saved in memory are 8x15 - eight pixels wide by fifteen pixels high. Chip-8 also comes with a font set, but it only contains the characters in the hex keyboard, so not overall the most useful font set.

CPU

Put it all together, and you get the CPU state.

class CPU {

constructor() {

this.memory = new Uint8Array(4096)

this.registers = new Uint8Array(16)

this.stack = new Uint16Array(16)

this.ST = 0

this.DT = 0

this.I = 0

this.SP = -1

this.PC = 0x200

}

}Decoding Chip-8 Instructions

Chip-8 has 36 instructions. All the instructions are listed here. All instructions are 2 bytes (16-bits) long. Each instruction is encoded by an opcode (operation code) and operand, the data being operated on.

An example of an instruction could be like this operation on two variables:

x = 1

y = 2

ADD x, yIn which ADD is the opcode and x, y are the operands. This type of language is known as an assembly language. This instruction would map to:

x = x + yWith this instruction set I'll have to store this data in 16-bits, so every instrution ends up being a number from 0x0000 to 0xffff. Each digit position in these sets is a nibble (4-bit).

So how can I get from nnnn to something like ADD x, y, that is a little more understandable? Well, I'll start by looking at one of the instructions from Chip-8, which is basically the same as the above example:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

8xy4 |

ADD Vx, Vy |

So what are we dealing with here? There's one keyword, ADD, and two arguments, Vx and Vy, which we've established above are registers.

There are several opcode mnemonics (which are like keywords), such as:

ADD(add)SUB(subtract)JP(jump)SKP(skip)RET(return)LD(load)

And there are several type of operand values, such as:

- Address (

I) - Register (

Vx,Vy) - Constant (

NorNNfor nibble or byte)

The next step is to find a way to interpret the 16-bit opcode as these more understandable instructions.

Bit Masking

Each instruction contains a pattern that will always be the same, and variables that can change. For 8xy4, the pattern is 8__4. The two nibbles in the middle are the variables. By creating a bitmask for that pattern, I can determine the instruction.

To mask, you use the bitwise AND (&) with a mask and match it to a pattern. So if the instruction 8124 came up, you would want to make sure the nibble in position 1 and 4 are on (passed through) and the nibble in position 2 and 3 are off (masked out). The mask then becomes f00f.

const opcode = 0x8124

const mask = 0xf00f

const pattern = 0x8004

const isMatch = (opcode & mask) === pattern // true 8124

& f00f

====

8004Similarly, 0f00 and 00f0 will mask the variables, and right-shifting (>>) them will access the correct nibble.

const x = (0x8124 & 0x0f00) >> 8 // 1

// (0x8124 & 0x0f00) is 100000000 in binary

// right shifting by 8 (>> 8) will remove 8 zeroes from the right

// This leaves us with 1

const y = (0x8124 & 0x00f0) >> 4 // 2

// (0x8124 & 0x00f0) is 100000 in binary

// right shifting by 4 (>> 4) will remove 4 zeroes from the right

// This leaves us with 10, the binary equivalent of 2So for each of the 36 instructions, I made an object with a unique identifier, mask, pattern, and arguments.

const instruction = {

id: 'ADD_VX_VY',

name: 'ADD',

mask: 0xf00f,

pattern: 0x8004,

arguments: [

{ mask: 0x0f00, shift: 8, type: 'R' },

{ mask: 0x00f0, shift: 4, type: 'R' },

],

}Now that I have these objects, each opcode can be disassembled into a unique identifier, and the values of the arguments can be determined. I made an INSTRUCTION_SET array containing all these instructions and a disassembler. I also wrote tests for every one to ensure they all worked correctly.

function disassemble(opcode) {

// Find the instruction from the opcode

const instruction = INSTRUCTION_SET.find(

(instruction) => (opcode & instruction.mask) === instruction.pattern

)

// Find the argument(s)

const args = instruction.arguments.map((arg) => (opcode & arg.mask) >> arg.shift)

// Return an object containing the instruction data and arguments

return { instruction, args }

}Reading the ROM

Since we're considering this project an emulator, each Chip-8 program file can be considered a ROM. The ROM is just binary data, and we're writing the program to interpret it. We can imagine the Chip8 CPU to be a virtual console, and a Chip-8 ROM to be a virtual game cartridge.

The ROM buffer will take the raw binary file and translate it into 16-bit big endian words (a word is a unit of data consisting of a set amount of bits). This is where that hex dump article comes in handy. I'm collecting the binary data and converting it into blocks that I can use, in this case the 16-bit opcodes. Big endian means that the most significant byte will be first in the buffer, so when it encounters the two bytes 12 34, it will create a 1234 16-bit code. A little endian code would look like 3412.

class RomBuffer {

/**

* @param {binary} fileContents ROM binary

*/

constructor(fileContents) {

this.data = []

// Read the raw data buffer from the file

const buffer = fileContents

// Create 16-bit big endian opcodes from the buffer

for (let i = 0; i < buffer.length; i += 2) {

this.data.push((buffer[i] << 8) | (buffer[i + 1] << 0))

}

}

}The data returned from this buffer is the "game".

The CPU will have a load() method - like loading a cartridge into a console - that will take the data from this buffer and place it into memory. Both the buffer and memory act as arrays in JavaScript, so loading the memory is just a matter of looping through the buffer and placing the bytes into the memory array.

The Instruction Cycle - Fetch, Decode, Execute

Now I have the instruction set and game data all ready to be interpreted. The CPU just needs to do something with it. The instruction cycle consists of three steps - fetch, decode, and execute.

- Fetch - Get the data stored in memory using the program counter

- Decode - Disassemble the 16-bit opcode to get the decoded instruction and argument values

- Execute - Perform the operation based on the decoded instruction and update the program counter

Here's a condensed and simplified version of how load, fetch, decode, and execute work in the code. These CPU cycle methods are private and not exposed.

The first step, fetch, will access the current opcode from memory.

// Get address value from memory

function fetch() {

return memory[PC]

}The next step, decode, will disassemble the opcode into the more understandable instruction set I created earlier.

// Decode instruction

function decode(opcode) {

return disassemble(opcode)

}The last step, execute, will consist of a switch with all 36 instructions as cases, and perform the relevant operation for the one it finds, then update the program counter so the next fetch cycle finds the next opcode. Any error handling will go here as well, which will halt the CPU.

// Execute instruction

function execute(instruction) {

const { id, args } = instruction

switch (id) {

case 'ADD_VX_VY':

// Perform the instruction operation

registers[args[0]] += registers[args[1]]

// Update program counter to next instruction

PC = PC + 2

break

case 'SUB_VX_VY':

// etc...

}

}What I end up with is the CPU, with all the state and the instruction cycle. There are two methods exposed on the CPU - load, which is the equivalent of loading a cartridge into a console with the romBuffer as the game, and step, which is the three functions of the instruction cycle (fetch, decode, execute). step will run in an infinite loop.

class CPU {

constructor() {

this.memory = new Uint8Array(4096)

this.registers = new Uint8Array(16)

this.stack = new Uint16Array(16)

this.ST = 0

this.DT = 0

this.I = 0

this.SP = -1

this.PC = 0x200

}

// Load buffer into memory

load(romBuffer) {

this.reset()

romBuffer.forEach((opcode, i) => {

this.memory[i] = opcode

})

}

// Step through each instruction

step() {

const opcode = this._fetch()

const instruction = this._decode(opcode)

this._execute(instruction)

}

_fetch() {

return this.memory[this.PC]

}

_decode(opcode) {

return disassemble(opcode)

}

_execute(instruction) {

const { id, args } = instruction

switch (id) {

case 'ADD_VX_VY':

this.registers[args[0]] += this.registers[args[1]]

this.PC = this.PC + 2

break

}

}

}Only one aspect of the project is missing now, and a pretty important one - the ability to actually play and see the game.

Creating a CPU Interface for I/O

So now I have this CPU that's interpreting and executing instructions and updating all its own state, but I can't do anything with it yet. In order to play a game, you have to see it and be able to interact with it.

This is where input/output, or I/O, comes in. I/O is the communication between the CPU and the outside world.

- Input is data received by the CPU

- Output is data sent from the CPU

So for me, the input will be through the keyboard, and the output will be graphics onto the screen.

I could just mix the I/O code in with the CPU directly, but then I would be tied to one environment. By creating a generic CPU interface to connect the I/O and the CPU, I can interface with any system.

The first thing to do was look through the instructions and find any that have to do with I/O. A few examples of those instructions:

CLS- Clear the screenLD Vx, K- Wait for a key press, store the value of the key in Vx.DRW Vx, Vy, nibble- Display n-byte sprite starting at memory location I

Based on that, we'll want the interface to have methods like:

clearDisplay()waitKey()drawPixel()(drawSpritewould have been 1:1, but it ended up to be easier doing it pixel-by-pixel from the interface)

JavaScript doesn't really have a concept of an abstract class as far as I could find, but I created one by making a class that could not itself be instantiated, with methods that can only be used from classes that extend it. Here are all the interface methods on the class:

// Abstract CPU interface class

class CpuInterface {

constructor() {

if (new.target === CpuInterface) {

throw new TypeError('Cannot instantiate abstract class')

}

}

clearDisplay() {

throw new TypeError('Must be implemented on the inherited class.')

}

waitKey() {

throw new TypeError('Must be implemented on the inherited class.')

}

getKeys() {

throw new TypeError('Must be implemented on the inherited class.')

}

drawPixel() {

throw new TypeError('Must be implemented on the inherited class.')

}

enableSound() {

throw new TypeError('Must be implemented on the inherited class.')

}

disableSound() {

throw new TypeError('Must be implemented on the inherited class.')

}

}Here's how it will work: the interface will be loaded into the CPU on initialization, and the CPU will be able to access methods on the interface.

class CPU {

// Initialize the interface

constructor(cpuInterface) {

this.interface = cpuInterface

}

_execute(instruction) {

const { id, args } = instruction

switch (id) {

case 'CLS':

// Use the interface while executing an instruction

this.interface.clearDisplay()

}

}Before setting up the interface with any real environment (web, terminal, or native) I created a mock interface for tests. It doesn't actually hook up to any I/O but it helped me to set up the state of the interface and prepare it for real data. I'll ignore the sound ones, because that was never implemented with actual speaker output, so that leaves the keyboard and screen.

Screen

The screen has a resolution of 64 pixels wide by 32 pixels tall. So as far as the CPU and interface is concerned, its a 64x32 grid of bits that are either on or off. To set up an empty screen, I can just make a 3D array of zeroes to represent all pixels being off. A frame buffer is a portion of memory containing a bitmapped image that will be rendered to a display.

// Interface for testing

class MockCpuInterface extends CpuInterface {

constructor() {

super()

// Store the screen data in the frame buffer

this.frameBuffer = this.createFrameBuffer()

}

// Create 3D array of zeroes

createFrameBuffer() {

let frameBuffer = []

for (let i = 0; i < 32; i++) {

frameBuffer.push([])

for (let j = 0; j < 64; j++) {

frameBuffer[i].push(0)

}

}

return frameBuffer

}

// Update a single pixel with a value (0 or 1)

drawPixel(x, y, value) {

this.frameBuffer[y][x] ^= value

}

}So I end up with something like this to represent the screen (when printing it as a newline-separated string):

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

...etc...In the DRW function, the CPU will loop through the sprite it pulled from memory and update each pixel in the sprite (some details left out for brevity).

case 'DRW_VX_VY_N':

// The interpreter reads n bytes from memory, starting at the address stored in I

for (let i = 0; i < args[2]; i++) {

let line = this.memory[this.I + i]

// Each byte is a line of eight pixels

for (let position = 0; position < 8; position++) {

// ...Get value, x, and y...

this.interface.drawPixel(x, y, value)

}

}The clearDisplay() function is the only other method that will be used for interacting with the screen. This is all the CPU interface needs for interacting with the screen.

Keys

For keys, I mapped the original hex keyboard to the following 4x4 grid of keys:

┌───┬───┬───┬───┐

│ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │ 4 │

│ Q │ W │ E │ R │

│ A │ S │ D │ F │

│ Z │ X │ C │ V │

└───┴───┴───┴───┘I put the keys in an array.

// prettier-ignore

const keyMap = [

'1', '2', '3', '4',

'q', 'w', 'e', 'r',

'a', 's', 'd', 'f',

'z', 'x', 'c', 'v'

]And create some state to store the currently pressed keys.

this.keys = 0In the interface, keys is a binary number consisting of 16 digits where each index represents a key. Chip-8 just wants to know at any given time which keys are pressed out of the 16 and makes a decision based on that. A few examples below:

0b1000000000000000 // V is pressed (keyMap[15], or index 15)

0b0000000000000011 // 1 and 2 are pressed (index 0, 1)

0b0000000000110000 // Q and W are pressed (index 4, 5)Now if, for example, V is pressed (keyMap[15]) and the operand is 0xf (decimal 15), the key is pressed. Left shifting (<<) with 1 will create a binary number with a 1 followed by as many zeroes as are in the left shift.

case 'SKP_VX':

// Skip next instruction if key with the value of Vx is pressed

if (this.interface.getKeys() & (1 << this.registers[args[0]])) {

// Skip instruction

} else {

// Go to next instruction

}There is one other key method, waitKey, where the instruction is to wait for a keypress and return the key once pressed.

CLI App - Interfacing with the Terminal

The first interface I made was for the terminal. This was less familiar to me than working with the DOM as I have never made any sort of graphical app in terminal, but it wasn't too difficult.

Curses is a library used to create text user interfaces in the terminal. Blessed is a library wrapping curses for Node.js.

Screen

The frame buffer that contains the bitmap of the screen data is the same for all implementations, but the way the screen interfaces with each environment will be different.

With blessed, I just defined a screen object:

this.screen = blessed.screen({ smartCSR: true })And used fillRegion or clearRegion on the pixel with a full unicode block to fill it out, using the frameBuffer as the data source.

drawPixel(x, y, value) {

this.frameBuffer[y][x] ^= value

if (this.frameBuffer[y][x]) {

this.screen.fillRegion(this.color, '█', x, x + 1, y, y + 1)

} else {

this.screen.clearRegion(x, x + 1, y, y + 1)

}

this.screen.render()

}Keys

The key handler was not too different from what I would expect with the DOM. If a key is pressed, the handler passes the key along, which I can then use to find the index and update the keys object with any new additional keys that have been pressed.

this.screen.on('keypress', (_, key) => {

const keyIndex = keyMap.indexOf(key.full)

if (keyIndex) {

this._setKeys(keyIndex)

}

})The only particularly weird thing was that blessed didn't have a any keyup event that I could use, so I had to just simulate one by setting an interval that would periodically clear the keys.

setInterval(() => {

// Emulate a keyup event to clear all pressed keys

this._resetKeys()

}, 100)Entrypoint

Everything is set up now - the rom buffer to convert the binary data to opcodes, the interface to connect I/O, the CPU containing state, the instruction cycle, and two exposed methods - one to load the game, and one to step through a cycle. So I create a cycle function which will run the CPU instructions in an infinite loop.

const fs = require('fs')

const { CPU } = require('../classes/CPU')

const { RomBuffer } = require('../classes/RomBuffer')

const { TerminalCpuInterface } = require('../classes/interfaces/TerminalCpuInterface')

// Retrieve the ROM file

const fileContents = fs.readFileSync(process.argv.slice(2)[0])

// Initialize the terminal interface

const cpuInterface = new TerminalCpuInterface()

// Initialize the CPU with the interface

const cpu = new CPU(cpuInterface)

// Convert the binary code into opcodes

const romBuffer = new RomBuffer(fileContents)

// Load the game

cpu.load(romBuffer)

function cycle() {

cpu.step()

setTimeout(cycle, 3)

}

cycle()There is also a delay timer in the cycle function, but I removed it from the example for clarity.

Now I can run a script of the terminal entrypoint file and pass a ROM as the argument to play the game.

npm run play:terminal roms/PONGWeb App - Interfacing with the Browser

The next interface I made was for the web, communicating with the browser and the DOM. I made this version of the emulator a bit more fancy, since the browser is more of my familiar environment and I can't resist the urge to make retro looking websites. This one also allows you to switch between games.

Screen

For the screen, I used the Canvas API, which uses CanvasRenderingContext2D for the drawing surface. Using fillRect with canvas was basically the same as fillRegion in blessed.

this.screen = document.querySelector('canvas')

this.context = this.screen.getContext('2d')

this.context.fillStyle = 'black'

this.context.fillRect(0, 0, this.screen.width, this.screen.height)One slight difference I made here is I multiplied all the pixels by 10 so the screen would be more visible.

this.multiplier = 10

this.screen.width = DISPLAY_WIDTH * this.multiplier

this.screen.height = DISPLAY_HEIGHT * this.multiplierThis made the drawPixel command more verbose, but otherwise the same concept.

drawPixel(x, y, value) {

this.frameBuffer[y][x] ^= value

if (this.frameBuffer[y][x]) {

this.context.fillStyle = COLOR

this.context.fillRect(

x * this.multiplier,

y * this.multiplier,

this.multiplier,

this.multiplier

)

} else {

this.context.fillStyle = 'black'

this.context.fillRect(

x * this.multiplier,

y * this.multiplier,

this.multiplier,

this.multiplier

)

}

}Keys

I had access to a lot more key event handlers with the DOM, so I was able to easily handle the keyup and keydown events without any hacks.

// Set keys on key down

document.addEventListener('keydown', event => {

const keyIndex = keyMap.indexOf(event.key)

if (keyIndex) {

this._setKeys(keyIndex)

}

})

// Reset keys on keyup

document.addEventListener('keyup', event => {

this._resetKeys()

})

}Entrypoint

I handled working with the modules by importing all of them and setting them to the global object, then using Browserify to use them in the browser. Setting them to the global makes them available on the window so I could use the code output in a browser script. Nowadays I might use Webpack or something else for this, but it was quick and simple.

const { CPU } = require('../classes/CPU')

const { RomBuffer } = require('../classes/RomBuffer')

const { WebCpuInterface } = require('../classes/interfaces/WebCpuInterface')

const cpuInterface = new WebCpuInterface()

const cpu = new CPU(cpuInterface)

// Set CPU and Rom Buffer to the global object, which will become window in the

// browser after bundling.

global.cpu = cpu

global.RomBuffer = RomBufferThe web entrypoint uses the same cycle function as the terminal implementation, but has a function to fetch each ROM and reset the display every time a new one is selected. I'm used to working with json data and fetch, but in this case I fetched the raw arrayBuffer from the response.

// Fetch the ROM and load the game

async function loadRom() {

const rom = event.target.value

const response = await fetch(`./roms/${rom}`)

const arrayBuffer = await response.arrayBuffer()

const uint8View = new Uint8Array(arrayBuffer)

const romBuffer = new RomBuffer(uint8View)

cpu.interface.clearDisplay()

cpu.load(romBuffer)

}

// Add the ability to select a game

document.querySelector('select').addEventListener('change', loadRom)The HTML includes a canvas and a select.

<canvas></canvas>

<select>

<option disabled selected>Load ROM...</option>

<option value="CONNECT4">Connect4</option>

<option value="PONG">Pong</option>

</select>Then I just deployed the code onto GitHub pages because it's static.

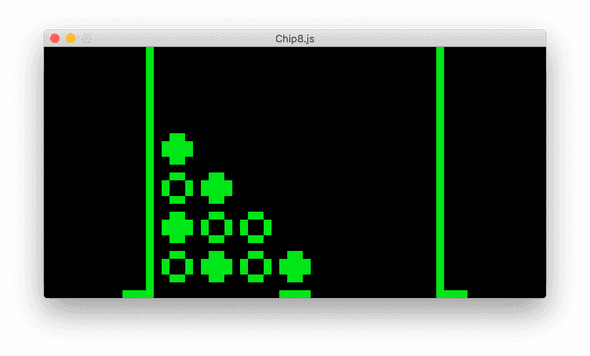

Native App - Interfacing with the Native Platform

I also made an experimental native UI implementation. I used Raylib, a programming library for programming simple games that had bindings for Node.js.

I consider this version experimental just because it's really slow compared to the other ones, so it's less usable, but everything works correctly with the keys and screen.

Entrypoint

Raylib works a bit differently than the other implementations because Raylib itself runs in a loop, meaning I won't end up using the cycle function.

const r = require('raylib')

// As long as the window shouldn't close...

while (!r.WindowShouldClose()) {

// Fetch, decode, execute

cpu.step()

r.BeginDrawing()

// Paint screen with amy changes

r.EndDrawing()

}

r.CloseWindow()Screen

Within the beginDrawing() and endDrawing() methods, the screen will update. For the Raylib implementation I accessed the interface directly from the script instead of keeping everything contained in the interface, but it works.

r.BeginDrawing()

cpu.interface.frameBuffer.forEach((y, i) => {

y.forEach((x, j) => {

if (x) {

r.DrawRectangleRec({ x, y, width, height }, r.GREEN)

} else {

r.DrawRectangleRec({ x, y, width, height }, r.BLACK)

}

})

})

r.EndDrawing()Keys

Getting the keys to work on Raylib was the last thing I worked on. It was more difficult to figure out because I had to do everything in the IsKeyDown method - there was a GetKeyPressed method, but it had side effects and caused problems. So instead of just waiting for a keypress like the other implementations, I had to loop through all keys and check if they were down, and append them to the key bitmask if so.

let keyDownIndices = 0

// Run through all possible keys

for (let i = 0; i < nativeKeyMap.length; i++) {

const currentKey = nativeKeyMap[i]

// If key is already down, add index to key down map

// This will also lift up any keys that aren't pressed

if (r.IsKeyDown(currentKey)) {

keyDownIndices |= 1 << i

}

}

// Set all pressed keys

cpu.interface.setKeys(keyDownIndices)That's it for the native implementation. It was more of a challenge than the other ones, but I'm glad I did it to round out the interface and see how well it would work on drastically different platforms.

Conclusion

So that's my Chip-8 project! Once again, you can check out the source on GitHub. I learned a lot about lower level programming concepts and how a CPU operates, and also about the capabilities of JavaScript outside of a browser app or REST API server. I still have a few things left to do in this project, like attempt to make a (very) simple game, but the emulator is complete, and I'm proud to have finished it.

Comments